Posted by Jim Adler, Chief Privacy Officer at Intelius

There’s been a lot of recent debate around the use of online names sparked by the

Google+ real names policy. The stark absolutism of this

debate baffles me, as if we had to choose between them. It’s a false choice. We

should have them all. As we map human social customs online, nuance and context

rule. Inflexible policies and binary choices are a cop-out. Life’s complicated

and more interesting that way. As I recently tweeted in a privchat:

There are legit use-cases for pseudonyms so they shouldn’t be banned. But

they are certainly unnatural for mainstream use. #privchat

This got me thinking about how many real names are typical for each person?

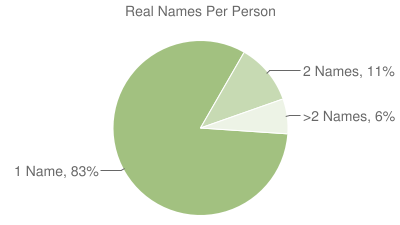

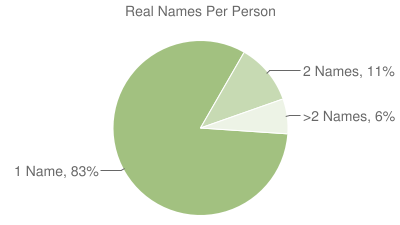

I did a quick look across the Intelius public-records corpus of a few hundred

million people and counted the number of real names per person. The results are

what you might expect:

The vast majority of people, 83%, have one full-name [Just to be clear, Sarah

Jessica Parker may also go by Sarah Jessica Broderick. Those would count as

two real names.] A significant minority, 11%, have two names. I imagine that

most of the people with two names are married women who are recently married or

simultaneously maintain their maiden and married names (typical of professional

women). It’s a little surprising that 6% have more than two names. I wonder how

many people in this set have criminal records?

So far, the nymwars debate has largely been framed around the 17%

that have more than one name. But there are strong pro and con arguments for

nyms, pseudonyms, and anonyms. What, the totality of human social engagement

can’t be pigeonholed into a single use-case? Hmm, Surprising.

Nyms

Whether offline or online, the vast majority of us build trusted

relationships and reputation around our real name. Real names are easy and

natural. I use my real name on Twitter, LinkedIn, and Facebook. One of Facebook’s best strategic moves was encouraging

use of real names. Generally, real names encourage real interactions and

weakens the barrier between offline and online experiences. However, requiring

real names is an 83% solution that’s fueling a Google+ backlash from the

other 17%.

Pseudonyms

There’s a host of reasons for pseudonyms, many of which have been cataloged during the recent nymwars. An example of a

pseudonym is Twitter’s PogoWasRight,

which is used persistently and has established respect within the privacy

community. Pseudonyms are not new as Samuel Clemens

proved more than 130 years ago.

The challenge with pseudonyms is that they are tough to manage. I know

several professional women that simultaneously maintain two legal names. They

are in a perpetual state of multiple account management—”which name did I use

for this account again?” I founded a startup several years ago that tried to crack this problem.

It’s a bear.

Anonyms

As for anonyms, they are distinct from pseudonyms. The intent with

pseudonyms is to build a long-lived identity that’s separate from our real

identity. In stark contrast are anonyms (e.g., fymiqcxw)

which are throw-away identities that in nearly all cases (except political

dissent) have nefarious intent. Online anonyms too often encourage what

psychologists call deindividuation. Nothing empowers a psychopath more than an

audience and a mask.

The key takeaway is—whether nym, pseudonym, or anonym—trust, accountability,

empathy, and civility are built around knowing whom you’re dealing with. As we

move through this continuum, we move away from “real” relationships. If that’s

your intent, fine. The nymwars debate is larger than the real name policies of

any social network. It is a further evolutionary move toward mapping our social

norms online. Sure, it’s messy. Most human endeavors are.

More from Jim Adler, Chief Privacy Officer at Intelius

Bookmark/Search this post with:

Delicious

Delicious Digg

Digg StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Propeller

Propeller Reddit

Reddit Magnoliacom

Magnoliacom Furl

Furl Facebook

Facebook Google

Google Yahoo

Yahoo Technorati

Technorati